History of Provan Hall

A Short History of Provan Hall

The land on which Provan Hall sits was owned by Glasgow Cathedral between the 1100s and 1560s, and during restoration of the current building, a roof timber from the 1200s was discovered, suggesting that elements of an older building had been reused. The oldest parts of the current buildings date to the 1470s, and saw adaptations and additions in the subsequent centuries.

The North Block has been restored to give a sense of its appearance in the 16th century, when one of Mary, Queen of Scots' courtiers, William Baillie, lived here with his wife Elizabeth. Later residents included Francis Hamilton, who gained fame for his 1626 poem dedicated to King James VI & I. The South Block, which houses our Welcome Hub and other multipurpose spaces, largely dates to the 1720s, and would have been home to figures such as Dr. John Buchannan (a somewhat mysterious gentleman farmer) and Reston and Elizabeth Mather (Reston was a champion horse breeder) in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

By the early 20th century, Provan Hall had fallen into disrepair, and it was two women who played crucial roles in saving it: Mary Holmes, its housekeeper, and Dreda Boyd, an author and heritage campaigner. They succeeded in seeing it restored in the 1930s and in 1938 it was taken on by the National Trust for Scotland. In the years after, the site was leased to the Corporation of Glasgow (later Glasgow City Council), and by the 1950s the caretaker was a man called Harold Bride, who just happened to have once been a wireless operator on the Titanic.

In 2008 the Friends of Provan Hall was formed which sought to secure the long-term future of the site, and a partnership between the city council, the Seven Lochs Wetland Park, National Trust for Scotland , the Friends and other organisations was established to bring about conservation and re-presentation work at the house. The partnership evolved to become the Provan Hall Community Management Trust which now cares for the site, and delivers community engagement projects, schools sessions, training schemes, exhibitions, volunteering opportunities and enables public access to Provan Hall.

Blogging Provan Hall's Past

Here you will find blogs by our staff, volunteers and from volunteers of Friends of Provan Hall. If you would like to find out more about a certain topic, please get in touch by using the details in our Contact Us page.

Walled Gardens Through Time

By Georgia Broughton

The Walled Garden

Kitchen gardens have been part of our homes and landscape dating back to the Roman times. They have undergone a transformation from medicinal herb patches in the Tudor period, to established structures in the Victorian times, before falling out of use in the 20th century. Attached to most stately homes and country houses, the kitchen garden has become almost synonymous with the National Trust.

Kitchen Gardens have always played a vital role in the running and history of country houses in the United Kingdom, they are significant not just to the house, but to the wider area as well. In the case of Provan Hall, due to its remote location, it would have played an important role in the running of the house, supplying tenants with fruit and vegetables throughout the year. Whilst kitchen gardens had been established in the 14th century, the rise of a formal garden began in the 17th century, as an increasing amount of stylistic interpretation began. They began to include topiary, furniture, fountains and other features. The gardens became larger and walls were built alongside the specific beds to maintain specific growth patterns and conditions for various fruits and vegetables. The walls were dual purpose, they kept out animals and thieves, whilst maintaining a sort of micro-climate optimal for food growth.

It is likely that Provan Hall had garden cultivation dating back to the mid-15th century, as the house was connected to Glasgow Cathedral. Anglo-Norman Monastic orders arrived in Scotland in the 12th century, bringing with them the skills required to cultivate fruit, vegetables and medicinal herbs. Based on this, it is quite likely that Provan Hall could have adopted monastic gardening techniques. Though the structures may have been swept away due to the multiple redesigns the house has undergone, part of the remaining terraces appear to have served as ornamental gardens for the house, and with the popularity of the walled garden for country houses, this would have evidently also been a place to grow food. The use of the surrounding land for agricultural production is well documented, and the south facing slope, which was probably unsuitable for arable cultivation would have been ideal for a garden.

Despite originally following Dutch and French practices, the many innovations introduced in the 18th and 19th centuries meant that the kitchen garden in the UK surpassed that of any in continental Europe. The decline of the country house estate in the 20th century led to many of such gardens falling into disrepair, whilst the structures crumbled with neglect and abandonment, as was the case with Provan Halls walled garden. Part of the renovation has included much garden work to bring the facilities back to a structure reminiscent of the historical one.

Kitchen Gardens are ornamental in providing a historical link to the past, and also provide us with a look into a sustainable and personal way of producing food. Provan Hall was fairly remote in comparison to the markets in Glasgow city and therefore would have required a certain level of self sufficiency when it came to food production, so the kitchen garden would have likely been a main source of food for the house. Surplus produce would have been preserved at the home for the winter months by drying or pickling, or, in the case of fruit, boiled into preserves and syrups. Despite the relative remoteness of Provan Hall, the surrounding area was the Bishop’s Hunting Ground, which leads to the assumption that Provan Hall may have been the location for feasting and entertainment during and after such pursuits, generating the need for self-sufficient cultivation of foods.

Now however, the kitchen garden has been restructured into something more ornamental, and with the growth of markets and 21st century large scale food production, the land has been repurposed to a feature more aesthetic choices rather than being regimented for food growth. Despite this, traces of the past remain today. The layout of the kitchen garden in the 17th century was one divided into quarters, a practice which meant that the soil could be worked on in the most direct means, a structure whose ghost you can still see in Provan Hall’s walled garden to this day.

Sources:

The Country House Kitchen Garden 1600-1950 by Anne Wilson, 2010

Stately Homes and Kitchen Gardens by Martin Philips, 2024 https://www.pressreader.com/uk/daily-express/20240429/283339002323189

Pot-to-plate dining: a history of the kitchen garden, the Savills Blog, 2023 https://www.savills.co.uk/blog/article/346615/residential-property/plot-to-plate-dining--a-history-of-the-kitchen-garden.aspx

Food For Thought by Emily Parker, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/members-area/members-magazine/food-for-thought/

Provan Hall Designed Landscape Study by Allison Allighan, The Garden History Society in Scotland, 2009

Easterhouse Crannogs - Ancient Dwellings

By Tom Rice-Hird (Provan Hall Volunteer)

An important feature of prehistoric Scotland was the Crannog. These were artificial islands, usually built on lochs, that were occupied over multiple generations. They were multi-purpose dwellings, serving as homes, agricultural working areas, trading hubs and social spaces, as well as a safe place to retreat to in times of danger. Their location on the water was vital and showcases the importance of waterways as a means of travel and communication.

Crannogs were exclusively built in Scotland and Ireland. The oldest date back to the Neolithic period, as far back as 3630 BC, but their construction peaked in Scotland around 800 BC to 200 AD. There is evidence to suggest that some were even still in use in the eighteenth century, although this was rare.

The Clyde and its surrounding waterways provided ample opportunity for the construction of Crannogs. As a vital route for travel and communication in the west of Scotland, plenty of Crannogs were built in the area. Near to Provan Hall, there are two such examples, on Bishop Loch and Lochend Loch.

Located a little over a mile east from Provan Hall, Bishop Loch is the site of a crannog discovered in 1898. Little is known about this site; indeed, even its location on the loch was not recorded, and it cannot be seen today due to the level of the water. Nonetheless, objects retrieved from the crannog include pottery, an iron-working crucible and a socketed iron axe head.

Another mile east is Lochend Loch, which has a crannog that is far better documented and researched. Excavations taking place in 1932 revealed a wooden structure buried under the mud at the bottom of the loch. The crannog had two floor layers. The higher level was built into the ruins of the one below; plenty of burned and charred wood was found, indicating that the original structure had partially burned down, and a second layer was constructed atop for a new dwelling.

This crannog was quite substantial; it is estimated that around 500 tons of rubble and other material was moved, and even included an area inside paved with stone. It is this area that items such as stone disks and a bracelet were found, alongside other evidence of human habitation such as bones and hazelnut shells. Today, the Crannog is below the water line but there are buoys marking its location and a visitor centre nearby.

The crannogs represent a unique part of Scottish history, and the ones present in Bishop and Lochend Lochs give us great examples near to Provan Hall. They are one of the few remnants of prehistoric Scotland that remain in a heavily industrialised and developed area, and add to the story of a continually inhabited Easterhouse.

References:

https://canmore.org.uk/site/44987/glasgow-bishop-loch#site-images

https://canmore.org.uk/site/45769/lochend-loch

https://www.culturenlmuseums.co.uk/story/crannogs-celts-and-coatbridge/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24680630?read-now=1&oauth_data=eyJlbWFpbCI6InRvbXJpY2VoaXJkQGdtYWlsLmNvbSIsImluc3RpdHV0aW9uSWRzIjpbXSwicHJvdmlkZXIiOiJnb29nbGUifQ&seq=18#page_scan_tab_contents

Left: Image of the remains of Lochend Crannog. Right: Image of reconstruction of a Crannog on Loch Tay

Mary Gossman Paints Provan Hall

By Provan Hall volunteer Alba Osa Parra

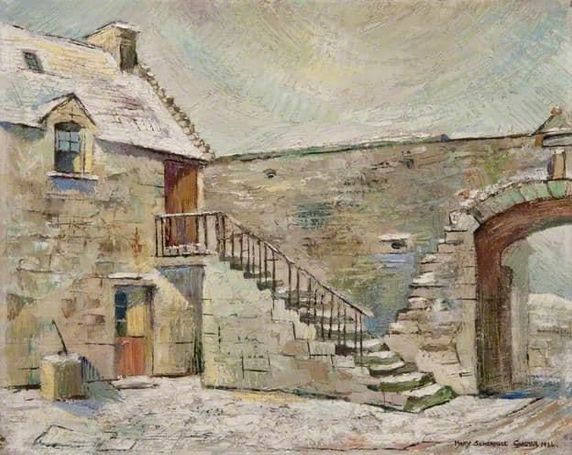

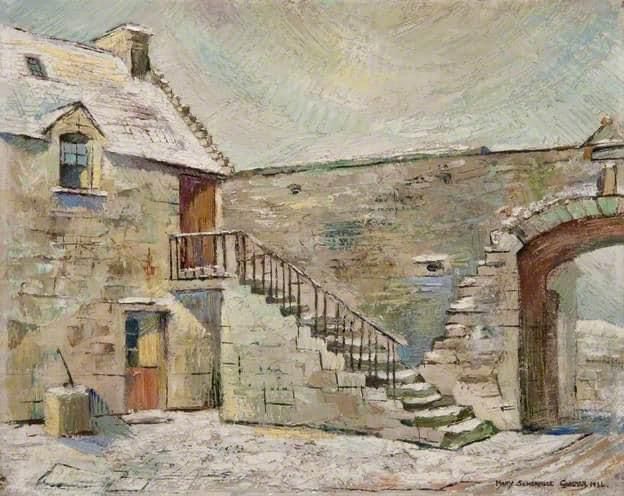

Mary Gossman was the artist who created this magnificent representation of Provan Hall in 1934.

Oil painting of Provan Hall by Mary Somerville Gossman, 1934.

Mary Gossman was an artist and writer born on 11 September 1911 in Glasgow. Daughter of Richard Gossman, a journeyman joiner, and Mary Jane Gossman. Throughout her life, she was a lover of the arts, especially drawing and painting. For this reason, she studied at the Glasgow School of Arts and was awarded a Diploma and Post Diploma. Her work was exhibited in the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts Exhibition in the Kelvingrove Art Galleries and the Society of Scottish Artists Exhibition in Edinburgh (The Herald, 1941: 4). She signed her work as "Mary Hislop Somerville Gossman" or "Mary Somerville Gossman", in honour of her mother, until she married Andrey MacDonald, after which she began signing as "Mary MacDonald."

Her passion for art led her to establish a small art shop in 1941 at 104 Main Street in Torrance, where she held exhibitions of her own and other artists’ work, and raised money for charities such as the Red Cross, Central War Fund and St Dunstan’s. On one occasion, the Director of Glasgow Art Galleries, Dr T. J. Honeyman, wrote a letter to Mary following a visit to her shop:

“This is to say how greatly I enjoyed my visit to your Art shop and to offer my very warm congratulations on your enterprise. There is no doubt that you merit the appreciation of all good citizens for what you are doing on behalf of war charities, but, apart from that, it appears to me that you are doing an excellent service for the cause of Art by making available such a comprehensive and catholic selection of your own work. The evidences of your career as a student and as a fully-fledged artist I found most interesting. I was especially struck by the fact that in various media you appear to be completely at home – oil, water- colour, pencil and ink. I wish your present exhibition every success and look forward to seeing more of your work in the future”.

Dr T. J. Honeyman (Stirling Observer, 1945: 5)

This is a testimony to Mary's great talent and her multifaceted work. Mary's work shows the influences of the Glasgow School of Art and artists such as the Glasgow Boys, especially in the subject matter of rural landscapes and the plein air technique used by the French Impressionist artists, which involved working outside the studio, in the open air and painting directly in front of the subject (MacDonald, 2000: 131-133). From the works that have survived, we can sense that Mary was interested in the natural scenes and historic buildings that she visited, such as Carmunnock Church, Kippen Parish Church, and an historic home in Berwickshire.

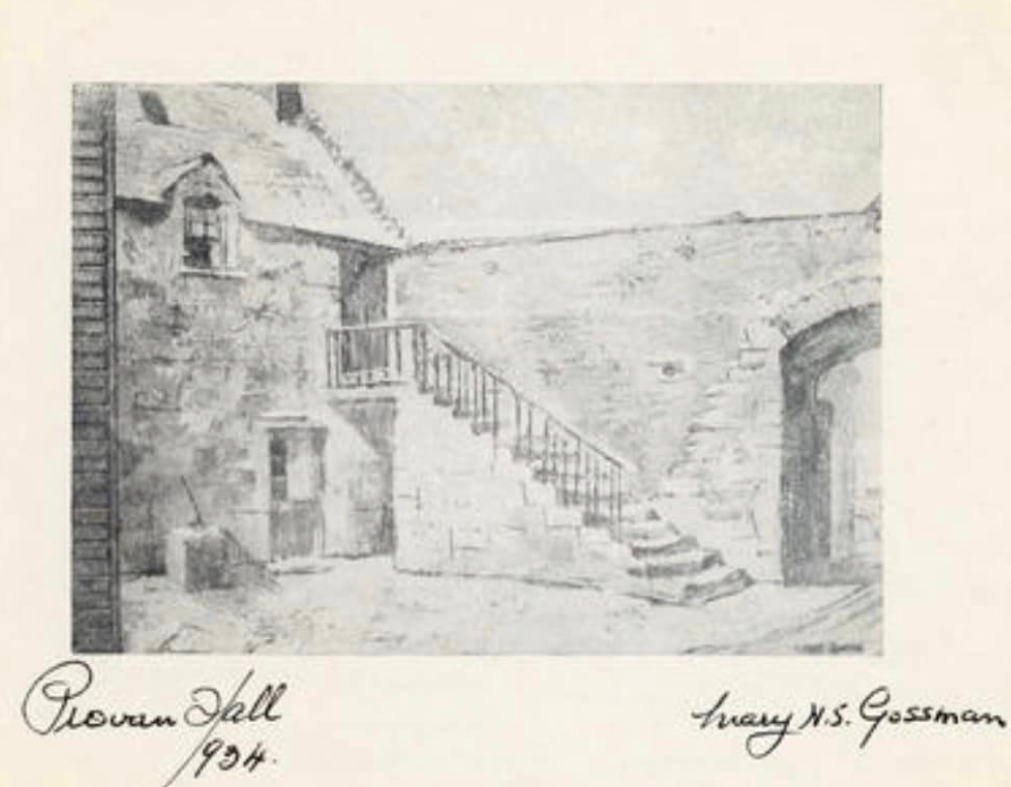

Her relationship with Provan Hall arose from a magnificent oil painting she made of this Early Modern building. Mary Gossman visited Mary Holmes (caretake and campaigner for Provan Hall, see blog below) with her mother as a child and fell in love with the house. After this, Mary visited Provan Hall several times and even began writing stories about it. In Glasgow Women's Library, an early sketch of this oil painting from 1934 is preserved.

Drawing. Sketch of Provan Hall by Mary Somerville Gossman, 1934. Glasgow Women’s Library, eHive.

Her talent did not end with painting, as she also excelled at needlework. Her work was displayed at the London Exhibition of Embroidery (The Herald, 1941: 4). She was also fond of writing, and numerous letters, articles and poems have been collected. Two of these articles were “Timeless Christmas Card” which was donated to the Glasgow Women’s Library and a short article for Stonehouse “An old word for Holy in German Heiligt”. Her poems include “Immortality or A Thought to Music” (1969):

“Hands Touch Piano Keys,

Gifted music on the breeze,

Dreams of distant lands arise,

Happiness of sunshine skies.”

Mary MacDonald (née Gossman, 1969)

Mary died in 1974 in Glasgow, aged 63. She was a woman of great talent and enterprise. And she was able to represent the beauty and history of Provan Hall in her work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We’d like to thank the Friends of Provan Hall for their help with this story. You can learn about the group here: https://www.facebook.com/provanhall

Sources

- Glasgow Women’s Library. Collection of Mary Hislop Somerville Gossman, Ehive.

- Macdonald, Murdo. Scottish Art. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

- Milngavie and Bearsden The Herald. “Torrance”, The Herald, 1941, p.4. The British Newspaper Archive.

- Stirling Observer, “Notelets”, Stirling Observer, 1945, p.5: The British Newspaper Archive.

Harold Bride: Titanic Hero at Provan Hall

By Provan Hall volunteer Alisa Ulanova

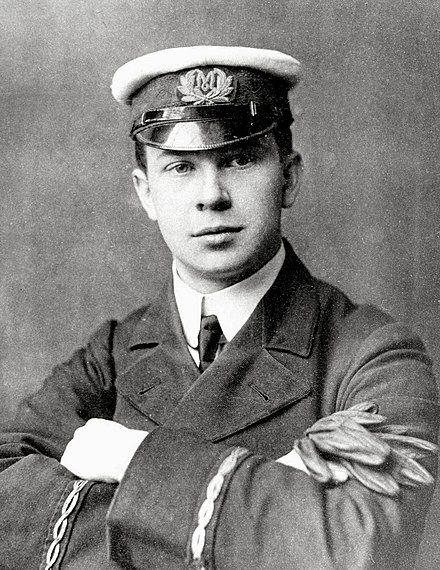

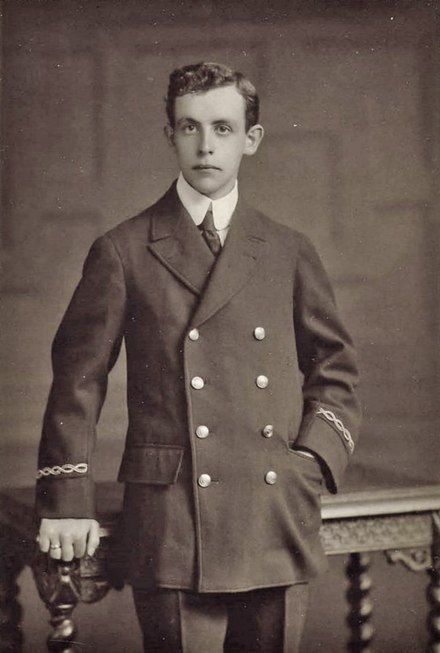

Harold Sydney Bride was a live-in caretaker at Provan Hall in the 1950s – but he acquired more fame as a Titanic wireless operator and survivor.

Bride was born on 11 January 1890 in Nunhead, London, to Arthur Bride and Mary Ann Lowe. He was the youngest of five children. The family lived in Bromley and Harold attended the local Langley Park School for Boys (then called Beckenham and Penge County Grammar School). He was interested in the new technology of transmitting wireless messages, and even assembled a noisy transmitter and massive antenna in the garden, angering the neighbours.

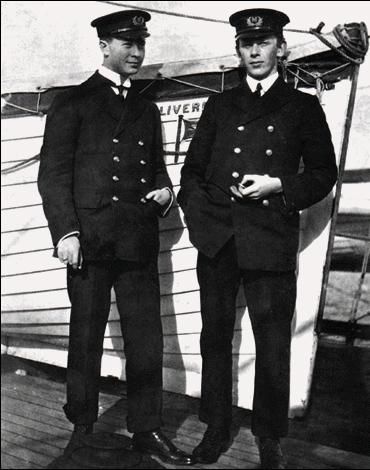

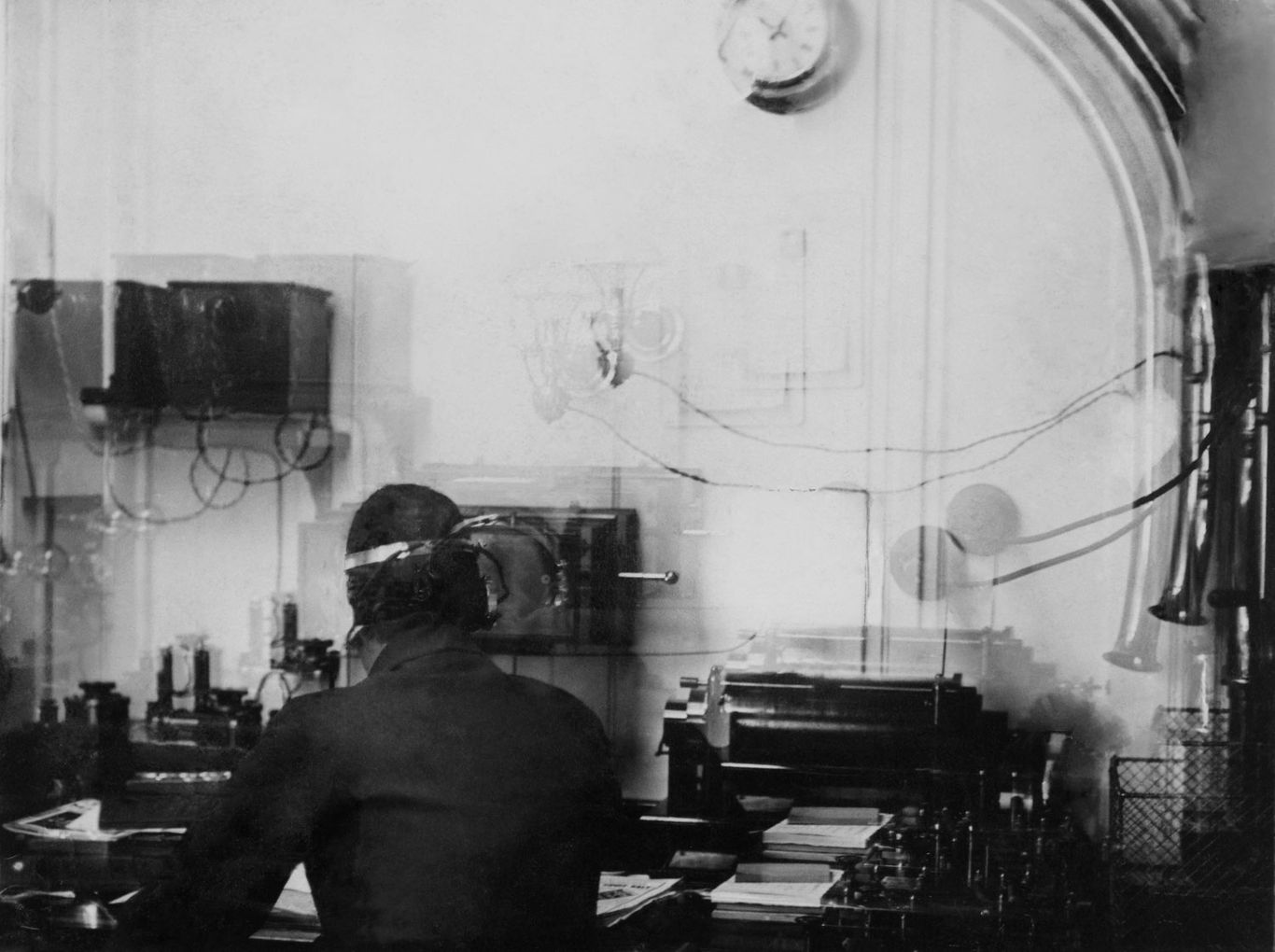

Harold Bride, John George "Jack" Phillips, and a reconstruction of the ship's radio rooms.

In July 1911 he finished training as a Marcony company operator and worked on several ships: the Haverford, the LaFrance, the Lusitania, the Anselm and the Beaverford.

In the beginning of the 20th century, the Titanic was the largest ship in the world and the most luxurious. The White Star Line company, which owned the ship, claimed she was "unsinkable."

On the 10th of April 1912 Harold Bride went on the voyage to New York from Southampton on the Titanic. His main duty was to relieve the senior operator, Phillips, while he was sleeping. On the 11th, the two men celebrated Phillips' 25th birthday with pastries from the first-class dining room.

On the night of tragedy, 14 April 1912, Bride went to bed early to relieve his colleague. Earlier in the day the wireless was working poorly. The operators spent a lot of time repairing it and finished just hours before the collision.

Throughout the day the ship received warnings of drifting ice from other ships. At 22:30 they received the sixth ice warning, but Phillips cut it off and signalled back: "Shut up, shut up, I'm working Cape Race". He was busy sending messages to Cape Race, Newfoundland, that were delayed while the telegraph equipment was being repaired.

At 11:40 pm the Titanic hit the iceberg. They didn't feel that something was wrong, except a slight jolt. Shortly after midnight the captain came in and told them to send "a regulation international call for help, just that." After about 5 minutes the captain came back asking Bride to send a distress call. Bride said to Phillips: "Send SOS, it's the new call, it may be your last chance to send it". They all laughed. Phillips, still laughing, changed the signal.

Harold Bride at work aboard the Titanic. Photo by Francis Browne, 11 April 1912

At 00:45 Titanic started to launch lifeboats. At 1:25 the operators sent out a message notifying other ships. Titanic was sinking by the bow with some inclination to the port side. The ships that heard the call responded, but even the Carpathia, the closest ship to the Titanic, couldn't reach them before morning.

The ship flooded and they put on more clothes and life vests. The next messages were sent: "Engine room getting flooded" at 1:35, and at 1:45 "Engine room full up to boilers." Bride caught a crew member trying to steal Phillips’ life vest, and fought him off. The captain told Bride and Phillips that they had done their job and were free from their duties, minutes before the Titanic sank.

Harold Bride 1912, Phillips, left.

Then they became separated. Bride helped launch the penultimate lifeboat. At 2:15 Titanic's angle started to increase rapidly, causing a big wave that washed over them. Bride found himself underneath the lifeboat, in the water, and climbed onto it. There was little space, with many crew members crowded on the upturned lifeboat. At 2:20 the Titanic sunk, 2 hours and 40 minutes after the collision. The sea was "dotted with people." Over 1,500 people died, and the sinking became one of the worst maritime disasters in history.

A 1912 illustration by Willy Stöwer.

The crew of the Mount Tample passing by Bride's lifeboat; Captain Edward Smith on the Titanic (11 April 1912) photo by Francis Browne; people at the pier 54, waiting for the Carpathia's arrival on April 18, 1912.

The survivors were rescued by the Carpathia in the early morning. Before Bride went up the rope ladder, he saw the Phillips' body and passed him to the crew. He later recalled how Phillips had worked tirelessly while everyone else was terrified, and had given his life to save others.

Before they reached New York, Bride helped Carpathia's exhausted operator send lists of survivors and messages of grief from Titanic passengers to their loved ones ashore. When they arrived, about 40,000 people stood on the wharves waiting for them.

As they disembarked, one of the police officers recognized Guglielmo Marconi, inventor of the wireless telegraph system, in the crowd, and began kissing his hands. If it hadn’t been for Marconi’s invention, no one would have survived. Seven hundred people had been saved thanks to the wireless telegraph.

Marconi 1909, with his invention, about 1902 (the receiver is on the left, and transmitter on the right), and in the wireless room of his yacht Electra, circa 1920.

Marconi and a journalist went to the Carpathia telegraph room, where they saw Bride still sending messages. He hadn't realized that the ship had reached land. His feet were wrapped in white bandages, one sprained, the other frostbitten. His lunch sat, uneaten, beside him. On the wall hung a photo of Marconi. Bride saw Marconi and smiled.

The journalist asked Bride for his version of the disaster. The next day Bride’s story was published in the newspaper and he became famous.

The US and British inquiries into the disaster, in which Bride testified, came to similar conclusions:

- The main cause of the disaster was weather conditions, with much more ice than usual in April.

- The captain did not give the order to reduce speed in the danger zone, despite many ice warnings.

- The number of casualties could have been reduced if the company had equipped the ship with enough lifeboats and planned the evacuation better.

- The Californian, much closer to Titanic than Carpathia, ignored the ship’s distress signal flares and could have rescued people much earlier.

The investigations led to a significant increase in safety requirements on ships.

Bride being carried down the Carpathia's gangway, US inquiry at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, and Marconi and Bride at the US inquiry.

After the Titanic disaster, Bride worked in a London post office, then in August 1912 as an operator on SS Medina on its route to Australia. In World War One, he worked on SS Mona's Isle, used as a net-laying ship for anti-submarine work. The crew of the ship also played a big part in saving people from a Dutch vessel that had been torpedoed.

Before the Titanic, Bride was engaged to a nurse called Mabel Ludlow, but he broke off the engagement in September when he met Lucy Downie, a teacher from Scotland. They married on the 10th of April 1920, moved to Stranraer, and had three children: Lucy, John, and Jeanette. To escape his Titanic fame, Bride became a traveling salesman for a pharmaceutical company. The family moved to Scone, and in the 1950s, to Glasgow.

Harold and Lucy lived in Glasgow until he died, aged 66, on 29 April 1956 at Stobhill Hospital, of bronchial carcinoma. He was cremated at Glasgow Crematorium and his ashes were scattered near its chapel. About twenty years later, Lucy’s ashes were scattered in the same place.

During his time in Scotland, Bride was a caretaker and manager of Provan Hall, and used to give tours of the building. If someone couldn't pay the entry price, he would let them pay half. He never gave up his love for the wireless telegraph and became an amateur radio enthusiast. Despite being a hero of the Titanic, Bride was modest and led a quiet life afterwards.

Resources:

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Bride

- https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume81_2013_number4/s/10414769

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sinking_of_the_Titanic

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lifeboats_of_the_Titanic#Collapsible_Engelhardt_Lifeboat_B_(port)

- https://oceanlinersmagazine.com/2021/01/11/harold-bride-titanic-wireless-operator/

- https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/titanic-marconi-and-wireless-telegraph

- https://www.google.com/amp/s/jamespaulmoody.tumblr.com/post/624704097279459328/titanics-wireless-operator-harold-brides/amp

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Mona%27s_Isle_(1882)#War_service

- https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/local-news/titanic-hero-lived-in-scone-20079980?int_source=amp_continue_reading&int_medium=amp&int_campaign=continue_reading_button#amp-readmore-target

- https://time.com/3787439/titanic/

- https://clickamericana.com/topics/events/the-titanic/titanics-wireless-sos-signal-and-response-1912

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guglielmo_Marconi

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Guglielmo-Marconi

- https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/image/MI_Titanic_Committee.htm

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Senate_inquiry_into_the_sinking_of_the_Titanic

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langley_Park_School_for_Boys

Witches of Scotland

By Provan Hall volunteer Hollie Wilson

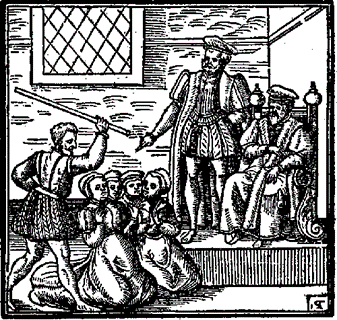

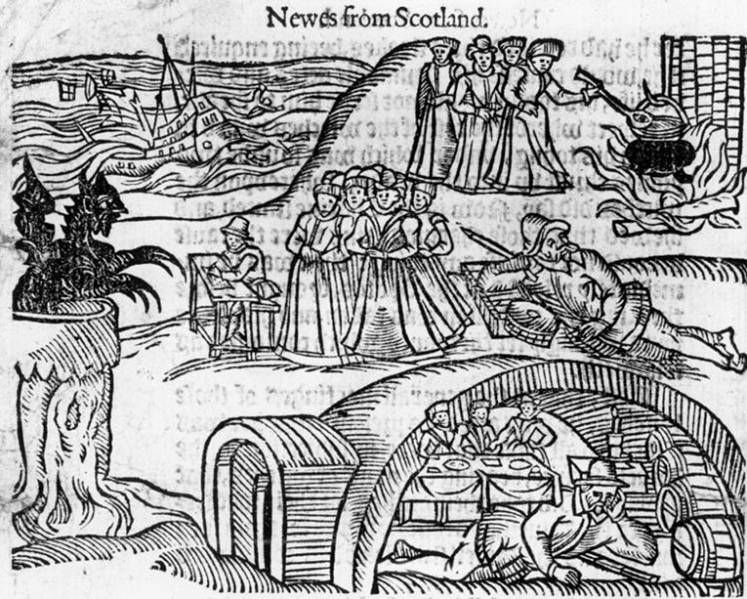

King James VI of Scotland presiding over a witch trial (National Museums of Scotland webpage).

The witch trials of Scotland are not as commonly thought about as those across wider Europe and of course, in the United States, but they were just as extreme. In fact, a 2005 paper stated that “few acts of the Scottish parliament can have had such deadly consequences” as the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 4 June, 1563. This Act led to the reported executions of an estimated 2,000 people over the next century and a half.

A lot of the accusations were based on religious fear, as was seen in the case of Francis Hamilton, who lived in Provan Hall at the time and accused his former fiancé of witchcraft (see our blog on Hamilton below). The Act was found to have its roots in the Protestant Church, which at the time was part of the larger Reformation of the country, including during the reign of Mary Queen of Scots. There was pressure for the Church to establish its own legislation, led by John Knox; he and many Protestants at the time accused Roman Catholics, believing they and the Catholic Queen to be in league with the Devil, of performing witchcraft in addition to adultery. However, there have also been reports of Catholics torturing and executing those they believed to be witches. The ‘panic’ and subsequent hunting of witches took hold of the country at large.

While there were some men accused during this period of ‘witch hunting,’ it was by and large women who were the ones targeted. Many of these women were seen as “charmers,” who claimed to heal illnesses and ailments through natural means. For many, the idea that someone could heal them also lent itself to idea that the same person could harm them, and throughout the 16th century, there was a continuing rise in ‘panic’ over finding witches and bringing them to supposed justice. This included one particular panic in North Berwick in 1590 and 1591, where a number of women were accused of plotting to kill King James VI of Scotland (the son of Mary, Queen of Scots and later King of England).

The ‘trial’ portion could include witness testimonies from neighbours, claiming to confirm the accused’s status as a witch, and confessions from the accused themselves at times. In fact, the 1649 trial of Patrick Watson found him accusing his own wife, perhaps with the idea that he could save himself; however, he would go on to be burned as a witch by “John Kincaid, a professional witch pricker who pricked suspects with a needle until he found a spot which did not bleed.” Sources state that in many cases, the end result had been all but decided already, and the confession was in fact more of a formality. The National Museum of Scotland holds information on many of the torture items used to elicit confessions, including thumbscrews and iron muzzles.

Today, there are some growing campaigns which seek to right these wrongs; Witches of Scotland are an organisation which have dedicated themselves to not only recording these incidents through their website, podcast and their interactive map (all linked below) but by campaigning for legislation to acknowledge these wrongdoings. While they note that the use of “pardoning” is incorrect as it implies that these men and women were in fact guilty of some crime (which has not been proven), it is the closest term which perhaps can be used in these circumstances.

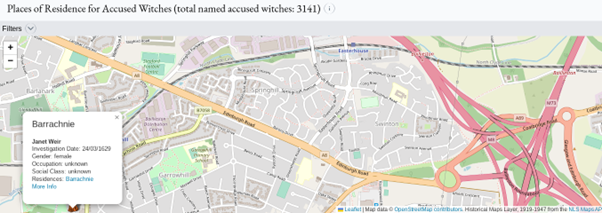

Below is a screenshot of the area around Provan Hall and Easterhouse - the closest recorded case on this map is in Barrachnie, but there may be even more, closer, that have not been found! In any case, it certainly shows how close to home the witch trials were, and the impact this could have had on the Easterhouse community and wider Glasgow area.

Places of Residence for Accused Witches, Barrachnie.

Sources:

- https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/11805860/The_Scottish_witchcraft_act.pdf

- https://www.witchesofscotland.com/

- https://www.ed.ac.uk/information-services/about/news/2019/interactive-witchcraft-map

- https://www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/scottish-history-and-archaeology/witchs-iron-collar/#:~:text=In%20the%20late%2016th,branks%20(an%20iron%20muzzle).

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/589913

- https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/shr.2002.81.2.240?journalCode=shr

Dreda Boyd - Provan Hall Saviour

By Provan Hall volunteer Alba Osa Parra

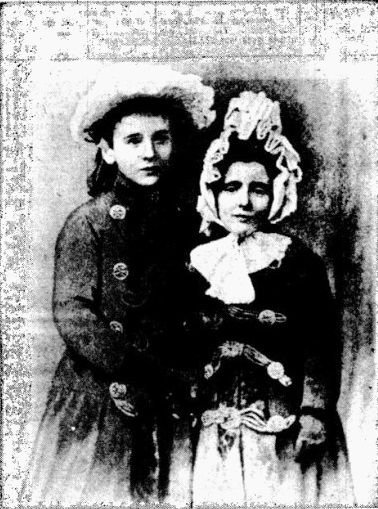

“A photograph of Miss Boyd, taken in the Garden of her Glasgow Home.” Photographer unknown. The Glasgow Herald, 1971.

“We can’t stay still – that’s the lesson of history. We must move forward”.

Dreda Boyd (1971)

Dreda Boyd, writer and philanthropist, was an important figure in the history of Provan Hall. She campaigned with Mary Holmes to save Provan Hall by raising funds for its restoration.

Etheldreda Holstein Boyd was born in August 1879 at Garrowhill House, Ballieston, an eastern suburb of Glasgow. Daughter of David Thomson Boyd, a local merchant, and Letitia DeHaven, an American from Philadelphia (Glasgow Herald, 1971:6), Dreda grew up in a time of economic boom in Glasgow. A flourishing shipbuilding industry helped Glasgow become one of Europe's most prosperous cities. Several prominent artists and cultural figures dominated the scene, including the Glasgow Boys, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and William Burrell. However, there was significant class disparity, with a lower life expectancy in poorer areas as a consequence of overcrowding (Maley, 2006).

Due to her mother's American background, Dreda considered her upbringing unconventional since she did not attend school regularly and had a governess (Glasgow Herald, 1971: 6). Her education, however, was focused on music, dance, fine arts, and modern languages, as was the case with many upper-class women of the late 19th century (UCL, 2023). She is mentioned in the archives as a student at the Royal Academy and Royal College of Music in 1893 (Scottish Leader,1893:6) and as a student at the University of Glasgow in the Modern Languages course in 1895 (The Herald and Lanarkshire, 1895:4). Due to her high social status, she travelled to other countries, such as Italy and the United States, to meet her relatives. When she was 18, she travelled to Germany with Helen, her younger sister, to study music, specialising in singing and piano. Her singing skills weren't as good as she had hoped, but she learned to write and speak German fluently during this time (Glasgow Herald, 1971:6).

“This charming portrait is of Dreda Boyd (left) and her sister Helen when they were about 12 and 10 years of age” Photographer unknown. The Glasgow Herald, 1971.

During an interview with the Glasgow Herald in 1971, she said that she was not concerned with "at-home days” when she was young but was passionate about history (Glasgow Herald, 1971:6). Her interest in the past led her to join various clubs such as the Old Glasgow Club, which was founded in 1900 as a gentleman's club to collect Glasgow history documents and books. Dreda joined on 19 October 1908 and was one of the first female members (Glasgow Old Society, 2023).

It was through her passion for old buildings and houses that she stumbled upon Provan Hall. She also became interested in another historic building, Provand's Lordship. Her desire to preserve history led her and like-minded friends to form the Provand's Lordship Society in 1908, a club dedicated to restoring and preserving this medieval house (Glasgow Herald, 1971:6). Dreda was society secretary for more than 30 years and was in charge, among other duties, of organising membership meetings for fundraising. High society gathered to dance, recite poetry, or watch theatrical performances and have tea and cakes. One of the most striking gatherings was the "Old Glasgow Dancing Assembly" in 1908 (The Queen, 1908:897), where all the attendees dressed up in 18th-century Georgian costumes and danced minuets and gavottes (The Graphic, 1908:667). Additionally, following the late 19th-century fashion for spiritualism, they also held esoteric meetings: “Some members formed a sort of inner circle – we called ourselves the ‘ghosts’ and every year we held a candlelit dinner in the old house, at which the ladies all wore white” (Glasgow Herald, 1971: 6).

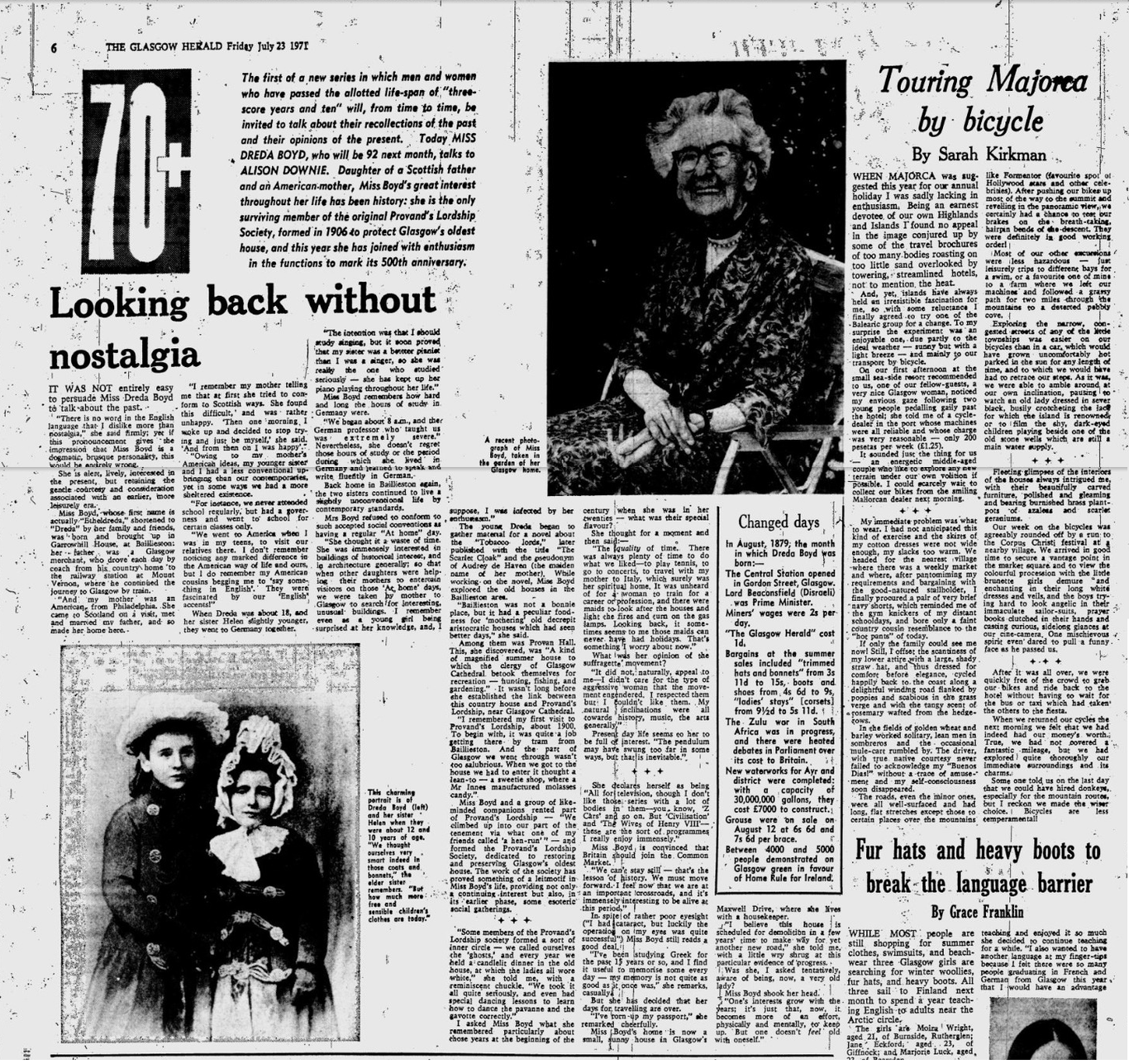

Dreda Boyd Glasgow Herald 23rd July 1971 p.6.

Writing was another of Dreda’s passions. During these meetings, Dreda had the opportunity to present her literary works including some plays: “A Queen’s Device” (1912) and “Lady Margaret Drummond” (1913) (The Scotsman, 1913:6). Under the pseudonym Audrey de Haven, a tribute to her mother, she wrote several short stories and novels: “Betsy Ann’s Siller”, “The Squire’s Wooing” (De Haven, A., 1903:2), “Maud Irving” (Bram, 2016), and “The Scarlet Cloak” (The Manchester Courier, 1907:10). In her work, she concentrates on the role of the female protagonist, bringing to light the universal themes of love, greed, and fear (De Haven, A., 1903:2). Around 1930, she wrote a series of articles focusing on Glasgow and its tourist attractions for SMT Magazine, a popular Scottish monthly travel magazine (The Scotsman, 1930:11; Edinburgh Evening, 1930:1; Broughty Ferry Guide and Advertiser, 1933:6).

Dreda also became interested in radio. In the mid-1920s she began to participate in various programmes talking about topics such as history, Glasgow, travel, and literature and also reciting short stories for children (Edinburgh Evening News, 1927:2; Paisley Daily Express, 1926:3).

Dreda dedicated her life to preserving the history of her hometown. Over the years she advocated for the preservation of Provan Hall and for the authorities to give it the importance it deserves, protecting it from the vandalism and neglect it suffered over the years. Together with Mary Holmes (see blog below) and with the help of the Old Glasgow Club, she managed to raise enough money to preserve this important building, celebrating Glasgow’s heritage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We’d like to thank John Dempsey and Katrina Murphy of the Friends of Provan Hall for their help with this story. You can learn about the group here: https://www.facebook.com/provanhall

We’d like to thank Brian D Henderson of Old Glasgow Club for his help with this story. You can learn about the group here: http://www.oldglasgowclub.org.uk/

Sources

- Bram, Eric M. The Mystery of Maud Irving: the “Wildwood Flower”: http://www.ergo-sum.net/music/MaudIrving.html

- Broughty Ferry Guide and Advertiser, “The S.M.T. Magazine for April”, Broughty Ferry Guide and Advertiser, 1933, p. 6: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002669/19330407/075/0006

- De Haven, Audrey. “The Squire’s Wooing”, Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser, 1903, p.2: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002391/19030221/030/0002

- Edinburgh Evening News, “AYC Wireless”, Edinburgh Evening News, 1927, p.2: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000452/19270103/045/0002

- Edinburgh Evening News, “General Noticies”, Edinburgh Evening News, 1930, p.1: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000452/19301104/011/0001

- Maley, Sonny, “The Book of the Month: The Old Closes and Streets of Glasgow”, Glasgow University Library Special Collections Department, 2006.

- Manchester Courier, “New Novels”, Manchester Courier, 1907, p. 10: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000206/19071203/142/0010

- Paisley Daily Express, “To-day’s Glasgow Wireless Programme” Paisley Daily Express, 1926, p.3: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001713/19260520/076/0003

- The Glasgow Herald, “Looking back without nostalgia” The Glasgow Herald, 1971, p. 6.

- The Graphic, “A revival of Old-time dances: Taking part in the minuet and gavotte at the Old Glasgow Dancing Assembly”,1908, p. 667: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000057/19081128/077/0019

- The Herald, “The Hamilton Herald and Lanarkshire Weekly News”, The Herald, 1895, p. 4: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002073/18950628/134/0004

- The Queen, “Old Glasgow Assembly”, The Queen, The Lady’s Newspaper, 1908, p.897: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002627/19081121/394/0065

- The Scotsman, “A Glasgow Historical Festival”, The Scotsman, 1913, p. 6: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000540/19131111/230/0006

- The Scotsman, “S.M.T. Magazine”, The Scotsman, 1930, p.11: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000540/19300531/084/0011

- The Scottish Leader, “Royal Academy and Royal College of Music” The Scottish Leader, 1893, p. 6: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0004178/18930425/106/0006

- University College of London, “Women and Education”, UCL Library Services, 2023.

Francis Hamilton & Isabel Boyd

By Provan Hall research volunteer Hollie Wilson

Newes from Scotland, 1590, National Museum of Scotland.

Francis Hamilton was born in Edinburgh, and from all sources did not seem to want for much. He was well-educated, attending Glasgow University alongside politicians and Lords, and was given Provan Hall in 1599 by his mother, Elizabeth Baillie. From his writings during this period, we can see that he was already very religious in his thinking, reflecting much of society in a time period where the church reigned over every part of life.

Burning of three "witches," Baden, Switzerland, 1585, by Johann Jakob Wick

In 1607, a contract was written up for Francis to marry Isabel Boyd, the daughter of the 6th Lord Boyd of Kilmarnock. In her thirties, she had already been widowed by her first husband John Blair three years before, leaving her with four children to raise and thankfully having a strong social standing to use to her advantage. It’s not known exactly why, but the marriage itself never happened. Instead, they both married others – Francis in 1609, Isabel by 1613 – and had children with those spouses.

It was many decades later that their paths would again intertwine, but this time things were far from romantic. Francis had spent the 1620s falling out of favour with his family by raising court actions against his father and sisters to avoid providing for them with the land known then as ‘Provand.’ He was unsuccessful in both instances, and by the end of the decade had begun losing areas of the land around Provan Hall. In 1630, he had appealed to the Convention of Estates, blaming his “financial misfortunes” on one Isabel Boyd, although this was ignored. In 1641, he tried once again, stating that she had “bewitched” him.

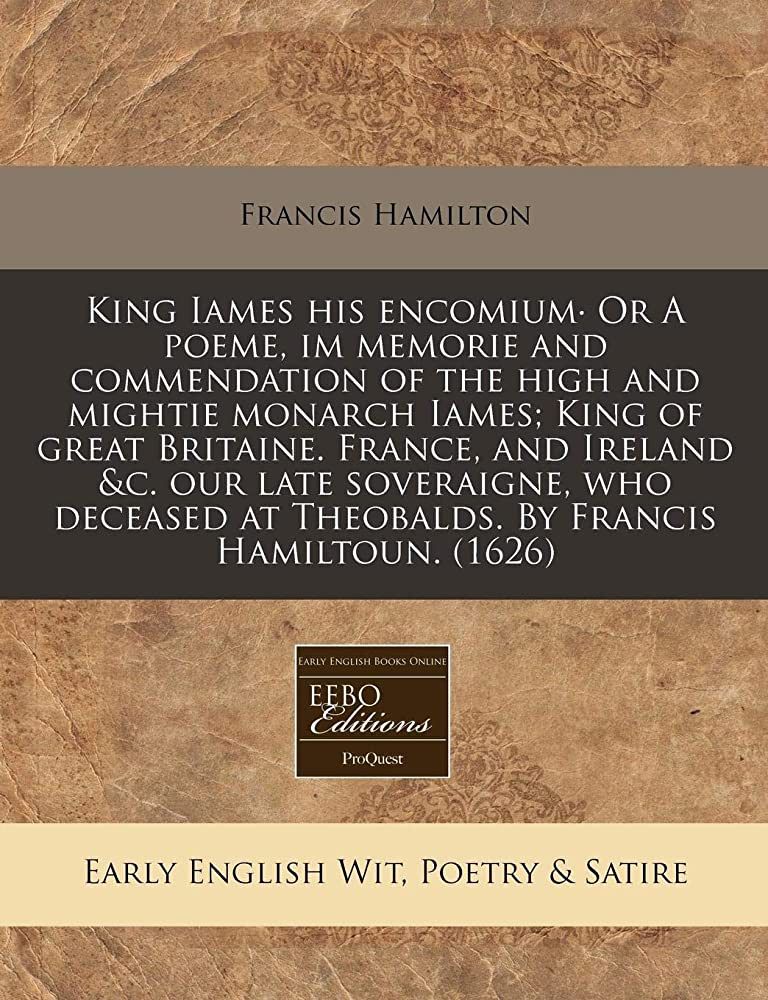

These accusations led to the creation of a poem by Francis: King James His Encomium, A Poeme, in memorie and commendation of the High and mightie Monarch IAMES, King of great Britaine, France, and Ireland &c. our late Soveraigne, who deceased at Theobalds, vpon Sunday the 27. of March.1625. This poem was most likely not viewed by many people, and there are only two copies of it currently available in Scotland. However, it indicates a lot of what may have caused Francis to accuse Isabel of causing his downfall.

Whether thy chance or choise makes thee to looke,

(Right reverend Reader) on this Poeme penn’d,

Accept my first essay, this litle booke,

Despise it not, nor spare it to amend.

So shall thou thanks receive, and gaine a friend,

And for thy paines have praise, the just reward

Of such as vertue favour, and befriend

The just and good intent. Nor misregard

One litle talent (being rightly vsed

To vertues praise), which shall not bring disgrace

To the possessour. Talents ten, abused,

Makes the abuser loose them and his place.

One litle Talent with right vse I crave,

Rather then Talents ten hid vp to have.

- King James His Encomium, A Poeme, in memorie and commendation of the High and mightie Monarch IAMES, King of great Britaine, France, and Ireland &c. our late Soveraigne, who deceased at Theobalds, vpon Sunday the 27. of March 1625 by Francis Hamilton

The cover of Hamilton's book of poetry.

According to records and his own writing, Francis was surrounded by religion; his father had been Christian, and numerous siblings of his married or were related to clergymen through those marriages. Accusations of witchcraft were often founded in religious fear, with those being accused often being lower class women known for working in herbal medicine or simply being outcasts.

This was perhaps where Francis failed – while there was no evidence of Isabel’s supposed witchcraft, this had not stopped many cases of innocent men and women being tried and even executed. Rather, the problem was who he was accusing. Isabel was the daughter of a Lord, most likely as well-educated as a woman could be at the time. She seems to not appear in any other legal issues, so probably lived an average life for a woman of her social class and standing as a wife and mother. In many ways, her social class saved her, or at least made it more obvious that Francis had attempted to use her as a scapegoat for his own failures.

The accusations, as a result, were largely ignored, and Francis’ poem, too. He would die only four years later in 1645. By this time, his father and wife had died; his father made no mention of Francis in his will, but did mention a potential daughter. Francis’ brother Edward also had to step in to support two of Francis’ children, indicating he could not provide for them. From his own will, it seemed Francis died destitute and alone, with no family mentioned. All of his worldly goods were given to a baker, to whom Francis owed an unpaid debt at the time of his death. According to the Journal of Northern Renaissance, this included: “The ‘summa of the inventar’ includes ‘ane old dornick boordcloath’, ‘twa old cushions’, ‘ane pair of old sheits’, ‘three old trunks and ane cabinet’, ‘ane stand of old black cloaths’, ‘twa pairs of old silk stockins with garters and rosis’.” A far cry from the young man given land, an upper-class education, with the world seemingly at his feet.

Sources:

- https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Boyd-2082

- https://jnr2.hcommons.org/2013/1620/

- https://electricscotland.com/history/nation/hamilton.htm

Who Built Provan Hall and When?

By John Dempsey, Friends of Provan Hall

Two of the most common questions asked about this curious old house is when it was built and who built it.

Cards on the table, we can’t say for certain. Various construction dates have been proposed. Claims are either broad e.g., 17th century or 1540s, or they are firm and precise e.g. 1450, 1460 or 1461. Some claim it was built before the Reformation in Scotland, some after. Some label the house Medieval, Late Medieval or Post-Medieval. Others make statements like "Glasgow's Oldest Building", clearly forgetting Glasgow’s Cathedral. There’s also the long running debate about whether Provan Hall or the Provand’s Lordship is the oldest. Proposed builders include the Bishops of Glasgow, James II, James IV, Bishop William Turnbull, and William Baillie.

So, with all this uncertainty and conflicting accounts, how can we go about answering the questions? One approach is to look at what archaeological and written evidence we are aware of and try to generate some ideas about how this amazing wee house came to be.

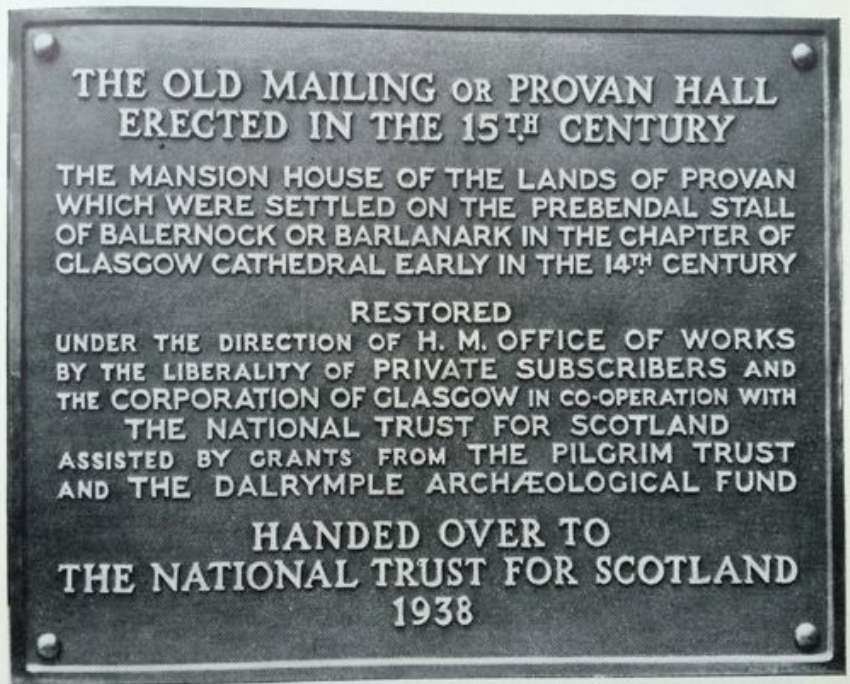

1. Plaque erected by NTS (now lost) and attached to the building following restoration in the 1930s (Sinclair 2016, 68)

2. Quote from Heritage Trail Leaflet (L&ES n.d.)

Archaeology

Let’s look first at the archaeological evidence. At present the consensus is the mid- 16th century, based primarily on architectural features and their similarity to other buildings of known age. In 2009 a building survey concluded that the North Range (the building with the turret) was constructed no earlier than this period. On Historic Environment Scotland’s website Canmore, there is likewise a broad agreement among archaeologists that the North Range is mid- 16th century. Even more recently, the restoration of the house was undertaken under the watchful eye of archaeologists, allowing them to observe, record and form new interpretations on an ongoing basis. So far, the middle of the 1500s again seems the most likely. These are of course interpretations (albeit by experienced archaeologists), and always open to debate and subject to change.

Is there any evidence for an earlier structure? Many don’t rule out the possibility of an earlier structure, but there just isn’t any evidence for one. There is, however, some tantalising evidence worthy of a thought. For one, there was the oak timber beam discovered above the 1st floor doorway during restoration. A method known as dendrochronology was performed using samples from the timber and the archaeologist concluded it was likely felled between 1259CE and 1295CE. It may also have an association with similar timber used at Glasgow Cathedral. This timber is thought to have been reused, meaning it functioned in some other way in another place or part of the house. Is this evidence of an earlier building? Or could it be a deliberate act motivated by superstition, warding off evil spirits at the threshold? More work is needed.

Some objects that have been found are also interesting. Several fragments of medieval pottery were recovered during archaeological investigations and watching briefs over the years. Do these show people living at Provan Hall earlier than we think?

What about the who? Does the archaeology supply any clues as to who built it? Well, what we don’t see archaeologically is any evidence for a royal ‘hunting lodge’ or anything characteristically ecclesiastical in nature that would tie these buildings to earlier centuries as they have been in the popular histories. This would have been a substantial structure of the time and needed lots of money and resources to build – even more so if a recent theory about there being a ‘lost tower’ is considered. Buildings such as these would have been a real projection of power and status, not just for posh living with some fashionable defensive features. It probably played a key role within the local society and economy. This points more towards private individual ownership.

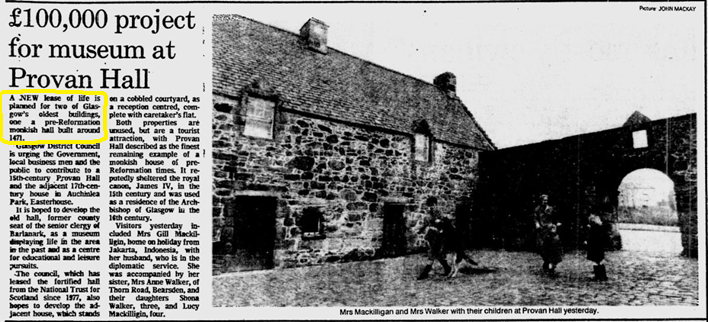

3. Glasgow Herald 6th Jan 1984.

4. Core Sampling in the North Range (Addyman and Mills 2022). 5. Reused oak timber above door lintel (Mills 2021, 19).

Written Sources

What about written sources then? Before the effects of the Reformation in Scotland, the lands on which Provan Hall were built were granted to the Dean and Chapter of Glasgow Cathedral with records covering this period from the 12th to the 16th century. These supply written evidence useful for exploring many topics – what they do not include is any reference to Provan Hall or other settlement anywhere on the land. Church records discuss other houses, so that rules out a bias in the records as far as ecclesiastical mansions are concerned.

The first possible glimpse of a building comes in 1562 when William Baillie, Lord Provand, fues the lands of Provan to Thomas Baillie of Ravenscraig. This document contains the phrase “Mains of Provan” and is a possible hint towards one or more farm buildings locally. However, by 1575 we have something more substantial. A charter signed by Lord Provand and his wife Elizabeth Durham at the "Hall of Provand" (p.6) provides the first substantial evidence for buildings on the site. It is from this period that references to the house then become more common, but we should also consider that written evidence is more abundant from this time.

6 Stained glass window in Parliament Hall Edinburgh commemorating the founding of the College of Justice. William Baillie's arms are shown in the top left of centre. (Wiki commons)

Some final thoughts...

So then, what is our current state of knowledge? And why does it matter when Provan Hall was built? To date, all the archaeological and written evidence we have suggests the house was built around the mid-1500s. Knowing this gives us some context for why it was built. The family most associated with the estate in this period is the Baillie family, who first drew income from the lands as canons of the Cathedral from c.1505 and latterly as a hereditary landowners from the crown. William Baillie, Lord Provand, was clearly making a name for himself as he climbed the legal ladder from notary public to Lord President of the Court of Justice in the 1560s, and took advantage of the changes Reformation afforded. At one point, he was a Baillie of Lamington and all indications are that he sought to establish a distinct Baillie of Provan Line – he retained the hereditary property rights in his feus, began legitimising his offspring and what better way to seal the deal than build for himself a handsome residence in the form of Provan Hall. I hope the debate continues, because speculation generates new ideas, new understandings, raises new questions and at the end of the day, makes it fun!!

Sources

- Addyman, T., and Mills, C. 2022. Provan Hall, Historic building recording and watching brief. In: Jennifer Thoms (ed), Discovery Excavation Scot, New, vol. 22, 2021. England, Cathedral Communications Limited. 83-84.

- Canmore. n.d. Glasgow, Auchinlea Road, Provan Hall (https://canmore.org.uk/site/44985/glasgow-auchinlea-road-provan-hall). Last viewed 19/4/23.

- Harrison, J. G. 2009. Provan Hall, Historical Documentary Evidence. Stirling, John G Harrison Historical Services.

- Land and Environmental Services. nd. Provan Hall Heritage Trail. Glasgow, Glasgow City Council.

- Mills, C.M. 2021. Provan Hall, Easterhouse, Glasgow: Dendrochronology Assessment Report. Edinburgh, Dendrochronicle.

- Sinclair, F. 2016. Provan Hall, Auchinlea Park, Glasgow Conservation Narrative. Glasgow, Fiona Sinclair Architect.

- Cook, M., Mills, C., and Thoms, J. 2020. Dendrochronology: Explore the science of tree ring dating. Forestry and Land Scotland. Forestry and Land Scotland.

Life in Easterhouse

By Provan Hall volunteer Gigi Lee

Interview with Thriving Places Community Connector Donna McGill

Donna McGill has lived all of her life in the East End of Glasgow and the majority of that living and working in Easterhouse, a suburb of Glasgow, Scotland. Her family moved there in 1969, seeking a better living environment during a time when overcrowding was a serious issue in Glasgow. The city planners had developed Easterhouse with new housing and designs, incorporating indoor bathrooms in each home. Donna fondly remembered how these advancements greatly improved her family’s living conditions, especially during a time when outside toilets were the norm in the older tenement buildings. She also enjoyed her close connection with nature in her childhood. Just across her family’s Easterhouse home was a farm, and she could see cows in the field, a massive tree with a swing, and rhubarb growing wild. This kind of green space was the ideal place for a child like her to run around and play outdoors.

Despite the improvements in their living conditions, Easterhouse was not without its challenges. The lack of community amenities created a culture of boredom and unrest, resulting in the rise of gang activity in the area. But in the early 1990s, several charities, such as the Phoenix Community Centre, FARE and Gladiators began their work in Easterhouse, offering diversionary, healthy group programs such as football and weightlifting for young people, which eventually helped to curb the gang activity. Today, local activities are thriving in Easterhouse, and Donna has created a comprehensive guide for residents to stay informed and navigate their community. The most up-to-date version of this can be accessed by clicking on this link.

Growing up in Easterhouse, Donna always hoped to contribute to her community. As a local Community Connector, she supports the development of local networks and helps residents to empower themselves by building their knowledge and skills. Her focus is on community, personal and social development, and she welcomes residents to seek her advice whenever they need it. Having grown up in the area, she understands the needs of the locals and can relate to their experiences. Donna believes in the ability of the local residents to achieve more than they believe they can and encourages them to aim high to attain their goals. She shares her personal story for a reason – Donna never imagined that she would go to university, but she did after years of effort, and now she has a meaningful job helping her community. She hopes that her story can inspire others to pursue their dreams and make positive changes in their lives and their community.

Donna is only one of the many people in Easterhouse who continue to contribute to the local community. Local residents are encouraged and supported to get involved and put in effort to build an even better community! Together, we can continue to make a positive impact and create a brighter future for Easterhouse.

With the opening of Provan Hall, Donna encourages local residents to take pride in our neighbourhood’s amazing historical resources. It is an opportunity for you to explore and preserve what you already have. Provan Hall is not just a historical landmark, but a part of the local community that deserves to be celebrated and cherished!

Mary Holmes - Caretaker and Campaigner

By Katrina Murphy, Friends of Provan Hall

Housekeeper to the Mather brothers of Provan Hall, and passionate preserver of this heritage gem.

Mary was born Mary Muir on 23 April 1894, at 36 Hayfield Street, Gorbals, Glasgow. Her parents were John Muir and Janet Graham, and she had six brothers and four sisters. At the time that she was born, her father was employed as a Carter (cart driver). He also laboured as a farm worker and ploughman. He worked in a number of different places but for many years worked for Professor McCall, founder of the Veterinary College of Blairtummock, on land which was very near to Provan Hall and where he met William Mather through a shared love of horses. William Mather was then resident at Provan Hall.

Mary was living with her parents on a farm at West Greenrig, Slamannan. William and his brother Reston visited the Muirs at the farm in autumn 1919, and two weeks later Reston Mather wrote to Mary asking her to come and work at Provan Hall as their elderly housekeeper had died.

The winter of 1919, when she was twenty-five years’ old, was the start of Mary’s Provan Hall journey, a journey which did not end until she left Provan Hall in 1955. Mary’s older sister Margaret had tried to persuade Mary not to go to Provan Hall, as she thought it was too large a job for such a young girl.

Mary’s role was housekeeper to William and Reston Mather until they both died in 1934. After the Mather brothers died, she took over as caretaker of Provan Hall along with her husband Adam Holmes. Mary had grown very close to the Mather brothers and was very fond of them both. She was well known to visitors for the teas she provided at Provan Hall when she was the caretaker.

In 1920, Mary’s brother John, who resided in Canada and was in the 1st Canadians, was seriously injured in battle in France. He decided to come home to Scotland. A year later, both Mary’s parents were ageing and her father infirm. Mr Henderson, Provan Hall’s gardener, had died and his cottage at Provan Hall was vacant, so Mary persuaded her parents and brother to move into the cottage along with their dog Paddy. They resided at Provan Hall cottage until the three of them died in 1931.

Then Mary met Adam Holmes, a talc miller by trade, and they married on the 18th of November 1933, in Glasgow. Adam moved into Provan Hall with Mary. He died there in 1954. Adam and Mary had one son, also named Adam, who was born in 1934. Sadly he died at the age of three weeks on 13 February 1934. He is buried in the Mather plot in Sandymount graveyard along with William and Reston Mather.

Mary got to meet many visitors to Provan Hall. In the time of William and Reston Mather she got to meet visitors such as politician Cunninghame Graham, artists George Houston and Sir David Young Cameron, and cousin Dr. George Ritchie Mather, Principle of the Royal Infirmary, who wrote the “Two Great Scotsmen”, who were all related to the Mathers. She also met Rev. Dr. Norman McLeod, author George Eyre Todd, the Wylies of Garthamlock, iron industrialists the Bairds of Gartsherry, and Dr. Hill B.L. of Barlanark House.

After the death of the last Lairds of Provan Hall, William and Reston Mather, Mary conceived the idea of turning her beloved Provan Hall into a tea room. At this time the house badly needed restoration. Mary contacted members of the Old Glasgow Club in which Miss Dreda Boyd, author of the "Scarlet Clock" was a member. They raised funds and Provan Hall was restored back to its former glory in 1936.

Visitors to Provan Hall tearoom signed the visitors book and some of these visitors included T.C.F. Brotchie, Miss Dreda Boyd, the Rev. Neville Davidson and his wife Mrs. Margaret Davidson of Glasgow Cathedral, Sir John and Lady Stirling Maxwell of Pollok House who wrote "Shrines of Scotland" with Provan Hall on the cover, Dr. Violet Robertson and artist Mary Gossman.

Mary finally left Provan Hall in 1955. She passed away at the age of 78 in Wishaw Hospital, Lanarkshire.

Sources

Scotland’s People (Birth, Marriage and Death Certificates)

Speculative Sketch by Pavo Interpretation.

Former visitors to Provan Hall.

Tearoom visitor book.

Todd's Well

By Annemarie Pattison, Friends of Provan Hall

Local landmark Todds Well, situated in the open ground below Conisburgh Rd has been known to locals for generations…but who or what was Todd?

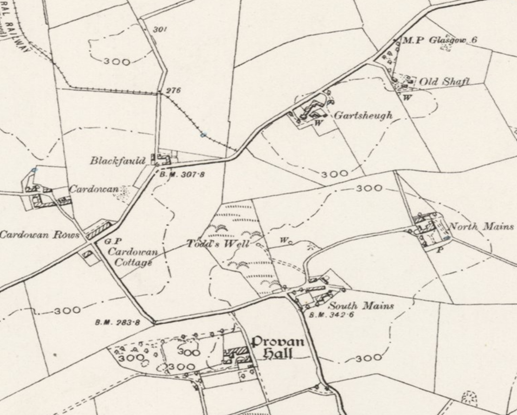

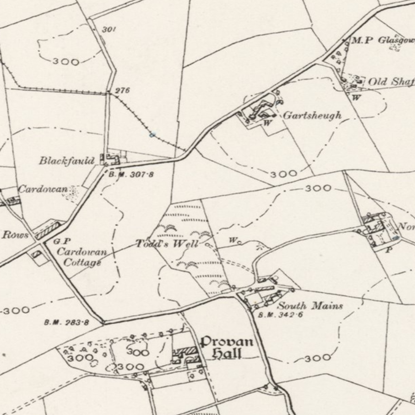

Research by Anne Marie of Friends of Provan Hall has discovered a local family named Todd who lived for over 100 years in a small farm which was part of the Provan Hall estate, in the Parish of Barony.

The residents of the ‘Big House’ are well known, with many books mentioning the Buchanans and Mathers who lived in Provan Hall from 1779 to 1934. Little has been discussed about the Wilsons who lived at North Mains and the Todds who lived at South Mains at the same time.

Records show that Janet Wilson married John Buchanan in 1816 at her home at North Mains, they then moved to the Big House and their family lived there until 1934. Three generations of Andrew Wilsons continued to live at North Mains until at least 1901. In fact, the Wilsons can be traced back for 4 generations living in the parish of Barony before Janet’s generation.

A third family lived in the area at the same time. The Todds lived at South Mains from at least 1776 when George Todd was born there. In 1841 Richard Todd (grandson of George) married Helen Wilson, niece of Janet Wilson.

Three sons of Richard and Helen are recorded on the 1901 census…but what about Todd’s Well?

An inscription at the location, erected in 1857, by R Todd is detailed in Scotland’s Places.

The 1888 Ordnance Survey map shows this area as being called Todd’s well. An earlier map (1882) shows this as Back o’Braes Well.

Was this change in name due to the 110+ years that the Todd family had used this well?

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.