Exhibitions

Opening in January 2026:

A View from Provan Hall: The Changing Landscape of the Seven Lochs

We host changing exhibitions exploring themes connected with Provan Hall and its environs. Our new exhibition opens in January 2026 and explores the built and natural heritage of the wider area surrounding Provan Hall over the last 2000 years, from crannogs to housing estates, peat bogs to farmland.

In partnership with Seven Lochs Wetland Park, and supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Historic Environment Scotland.

Exhibition blog

Witches' Marks

By Lauren McCarthy, Collections and Engagement Assistant

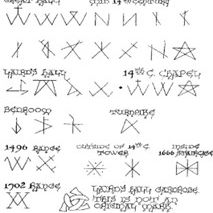

As you approach Provan Hall’s front entrance, you may notice some unusual markings on the inside of the stone archway, as pictured in Figure 1. Some have speculated that these are Masons’ marks. Masons have been involved in the construction of buildings and sculptures for thousands of years, using stone as the primary material. These skilled craftsmen would carve their initials or personalized symbols to enable them to identify their own work and distinguish it from the work of others, essentially acting as a signature. When literacy rates were low, these symbols would have conveyed important messages to construction workers, ensuring stones were assembled into the structure correctly. Pictured in Figure 2 are a series of typical masons’ marks found in Scottish buildings.

There is a clear uniform structure to masons’ marks which have been precision cut with sharp tools. When compared to the crude diagonal lines etched into the stonework at Provan Hall, they seem uncharacteristic of the work of a skilled artisan.

Upon further investigation, the marks at Provan Hall seem to more closely resemble apotropaic marks, otherwise known as witches’ marks, found on buildings across the UK. The stone archway dates to the 17th century when the Scottish Witch Trials were most intense. The marks themselves, however, are much more difficult to date. Apotropaic magic, deriving from the Greek word apotrépō meaning ‘to ward off’, refers to a type of protective magic intended to repel evil spirits. It involves a variety of rituals which have been globally observed throughout history. Witches’ marks were a common form of ritual protection in which symbols or patterns were carved into the stonework or woodwork of historic buildings. They are usually found at the thresholds of buildings to prevent witches and evil spirits from entering, thus protecting inhabitants and visitors from harm. It remained common practice to carve protection symbols into buildings in the UK until the early 1800s when superstition was still prevalent among many communities. These marks can take many forms but in Britain they most commonly take the shape of hexafoils, otherwise known as daisy wheels (a six-petal flower symbol enclosed within a circle). The hexafoil, as shown in Figure 3, is an ancient solar symbol and, as such, is representative of sunlight, keeping darkness and evil at bay.

During the Reformation of the mid-16th century, Catholics had to practise their faith in private to avoid persecution. Marian symbols, a variation of protection marks, were carved into buildings at this time containing the overlapping letters V and M for the Virgin Mary (or AM for Ave Maria). These symbols were thought to invoke the protection of the Virgin Mary and ward off evil. Craftsmen’s marks were used for centuries across different trades and in a similar way to stonemasons, carpenters etched Roman numerals into the timber frames of buildings to ensure they were installed correctly. Apotropaic markings on the wooden frameworks of buildings were similar to those found on stonework, with the addition of taper burn marks. These were specific to highly flammable timber buildings which commonly burned down in the early modern period when open flames were used for lighting, heating, and cooking. Teardrop shaped marks were deliberately charred into the timber to protect the building from fire.

Horizontal lines (like the ones at Provan Hall) along with boxes, and mazes are other forms of protection marks, thought to trap evil forces such as witchcraft. The largest discovery of witches’ marks in Britain can be found at Cresswell Crags in the East Midlands, shown in Figure 4. These caves date back over 600,000 years and its walls and ceilings are decorated with a plethora of protection symbols. Witches’ marks are notoriously difficult to date but doing so might enable a greater degree of certainty as to whether they are simply maker’s marks, or something else. The markings at Provan Hall are not as easily identifiable as hexafoils, casting greater uncertainty on their true meaning. However, given that Provan Hall has withstood over 500 years of history and even has a personal connection to the witch trials through Francis Hamilton, it is very possible that these lines have indeed been etched into the stonework to ward off evil spirits, demons, or witches.

After comparing the markings at Provan Hall with a wide variety of mason’s marks and other apotropaic marks, they certainly seem more typical of the latter. Mason’s marks, like carpenter’s marks, have a much higher degree of uniformity and are more strategically placed. Conversely, witch’s marks consist of more crudely engraved lines and their placement at entry points of buildings is consistent. The location of the marks at Provan Hall, combined with their lack of structure, make it highly plausible that they are indeed witches’ marks. That said, without concrete corroborating evidence, this remains a subject for debate.

Fig. 1. Photograph of markings at Provan Hall’s front entrance.

Fig. 2. Typical masons’ marks found across Scotland (Scottish Castles Association).

Fig. 3. Conjoined hexafoil marks to confuse or trap witches (Historic England).

Fig. 4. Various witches’ marks at Cresswell Crags (Creswell Heritage Trust).

Sources

Archiwest (2021) “Witches, Carpenters & Masons - what’s in a mark?” Available at: https://www.archiwest.co.uk/post/halloween-witches-marks.

Bishop’s House (n.d.) “The Secret Markings of Bishops’ House”. Available at: https://bishopshouse.org.uk/the-secret-markings-of-bishops-house/#:~:text=Daisy%20wheels%20are%20circles%20with,to%20be%20good%20luck%20symbols.

Clarke, David (2020). Marks of the Witch: Britain's ritual protection symbols. Fortean Times (392), 36-43. [Article]

Cresswell Crags (2019) “Hidden Witch Marks Revealed”. Available at: https://www.creswell-crags.org.uk/news-archive/hidden-witch-marks-revealed.

Cresswell Crags (2019) “Largest Discovery of Witch Marks in Britain at Cresswell Crags”. Available at: https://www.creswell-crags.org.uk/news-archive/largest-discovery-of-witch-marks-in-britain-at-creswell-crags.

Historic England (n.d.) “What Are Witches’ Marks?” Available at: https://historicengland.org.uk/whats-new/features/discovering-witches-marks/what-are-witches-marks/.

Historic England (n.d.) “Witches’ Marks: Apotropaic and Carpenters’ Marks”. Available at: https://historicengland.org.uk/whats-new/features/discovering-witches-marks/types-of-marks.

Hoggard, Brian (n.d.) “Protection Marks”. Available at: https://www.apotropaios.co.uk/protection-marks.html.

National Trust (n.d.) “Warding Off Evil with Witch Marks”. Available at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/discover/history/warding-off-evil-with-witch-marks.

Scottish Castles Association (n.d.) “Masons’ Marks Project”. Available at: https://scottishcastlesassociation.com/news/news-features/masons-marks.htm.

Sinclair, Gwen (2021) “Masons’ Marks Talk by Iain Ross Wallace MA”. Dundonald Castle and Visitor Centre. Available at: https://dundonaldcastle.org.uk/masons-marks-talk-by-iain-ross-wallace-ma/

University of Warwick (n.d.) “Medieval Masons’ Marks”. Available at: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/scapvc/arthistory/people/ja/research/masonsmarks/.

Exhibition blog

Inspired by our exhibition on Scottish folklore and witchraft, one of our volunteers, Rowan Liddle, explores the links between fairies, witches and magic...

By Rowan Liddle, volunteer

On the evening of May 14th, 1692, Robert Kirk, minister of Aberfoyle and author of the yet to be published book ‘The Secret Commonwealth,’ set out for a walk across Doon Hill, from which he would never return. His body was discovered later, where it appeared he had died of a heart attack at the age of 48, leaving behind his pregnant wife and child. Legend states, however, that he was instead kidnapped by fairies, either leaving his physical body behind when entering the fairy realm through a fairy ring or leaving behind a fake body. At the time, Doon Hill was a well-known fairy habitat, and Kirk’s book ‘The Secret Commonwealth,’ seemed to have attracted unsavoury attention from the fairy folk.

‘The Secret Commonwealth’ was treatise on a variety of local legends, from phenomena such as second sight, an ability to see the future and fairies, to fairy lore. Attempting to reconcile the scientific and supernatural, Kirk proposes a scientific explanation for faeries. This was drawn from various accounts made by his parishioners. Fairies are referred to by a variety of names in the book, such as the Gaelic ‘sith,’ the ‘sluagh maith’ (good people), and the ‘lychnobious people’ (those living by lamplight). Kirk suggests that fairies were a form of intermediate spirits, a classification that was below angels and above humans. They were depicted as having the same capacity for evil as humans, being neither innately good nor bad. Kirk goes on to describe how fairies interacted with the world, from how they slept, reproduced, ate, down to the minutiae of how they created their own clothing. Kirk suggests that fairies were organised in tribes and orders, and had ceremonies such as marriages and burials. Among books discussing the supernatural, The Secret Commonwealth is notable for its unabashed engagement and acceptance of local folklore, which was considered radical among the educated elite. It was also one of the earliest usages of the term ‘fairy tale,’ going on to shape depictions of fairies long after its post-humous publication. The depth and detail of his work is said to have angered the fairy folk, who then took him for revealing their secrets.

Following his alleged kidnapping, Robert Kirk appeared as an apparition at the christening of his son. He then urged his cousin, Graham of Duchray, to release him by casting a dirk over his shoulder, a type of Scottish dagger, as it was believed that fairies were allergic to iron. However, when the time came, his cousin was so shocked by his appearance that he panicked, and failed to throw the dirk. Kirk was left trapped in Elfhame, the home of fairies, where he was forced to become the chaplain of its Queen. As legend goes, when his coffin was opened later, it was filled with rocks.

Currently Provan Hall is running an exhibit on Witchcraft which describes in part how witchcraft was linked to historical Scottish folklore and magic belief, such as fairies. With the traditional time-dilation of the fairy realm, as centuries have passed in human world, as little as three weeks may have passed in Elfhame, with Kirk barely aging. In Aberfoyle, people still visit Doon Hill, leaving ribbons and notes seeking luck or commemorate a loved one, on a pine tree that is believed to hold the spirit of Robert Kirk.

Images: Top: Morgan, W. (circa 1870-1880) ‘A Fairy Ring’ The Leicester Gallery; Bottom: See Loch Lomond (2025) ‘Walking Guide For Doon Hill Aberfoyle’

References:

- Atlas Obscura. (2025). Doon Hill and Fairy Knowe. [online] Available at: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/doon-hill-fairy-knowe [Accessed 13 Jul. 2025].

- Go Aberfoyle. (2021). Doon Hill Faerie Tree - Go Aberfoyle. [online] Available at: https://www.goaberfoyle.co.uk/attractions/doon-hill-faerie-tree/ [Accessed 22 Jun. 2025].

- Henderson, L. (2016) The (super)natural worlds of Robert Kirk: fairies, beasts, landscapes and lychnobious liminalities

- Hunter, M. (2001) ‘Robert Kirk’s The Secret Commonwealth and his “A Short Treatise of the Scotish-Irish Charms and Spells”’, in The Occult Laboratory: Magic, Science and Second Sight in Late Seventeenth-Century Scotland. Boydell & Brewer, pp. 77–117.

- MacQueen, D. (2019). Robert Kirk ‘The Fairy Minister’. [online] Transceltic - Home of the Celtic nations. Available at: https://www.transceltic.com/scottish/robert-kirk-fairy-minister.

- Manwaring, K. (2021). Performing Kirk: a search for authenticity in the dramatisation of the life of the ‘Fairy Minister’, Reverend Robert Kirk 007-Performing-Kirk - Kevan Manwaring.pdf

- Morgan, W. (circa 1870-1880) ‘A Fairy Ring.’ [Watercolour with white heightening on paper] The Leicester Gallery. Available at: https://www.leicestergalleries.com/browse-artwork-detail/MTY3NjI= [Accessed 29 Jun. 2025]

- See Loch Lomond (2025). [online] Walking Guide For Doon Hill Aberfoyle. Available at: https://www.seelochlomond.co.uk/discover/walking-guide-for-doon-hill-aberfoyle [Accessed 22 Jun. 2025].

- Warner, M. (2019) 'Extreme possibilities: Robert Kirk's remarkable study of fairy lore clashed with the scepticism of 17th-century society--but its spirit of active wonder speaks to our new age of enchantment', New Statesman, 148(5478), 46+, available: https://link-gale-com.ezproxy1.lib.gla.ac.uk/apps/doc/A593800871/AONE?u=glasuni&sid=summon&xid=32737cf4 [accessed 22 Jun 2025].

Exhibition blog

Witch iconography

By Anna Hartness, Research Volunteer at Provan Hall

Throughout history, witches have been represented in many different media forms. From 16th century woodcuts to modern day Hollywood films, they have always had a very stereotypical image that has stood the test of time. When you dressed up in that pointed black hat one Halloween, did you ever wonder why? Well now you can find out why witches are depicted this way and find out the historical significance of your Halloween costume.

Hats, Broomsticks & Cauldrons – The top three accessories of a stereotypical witch are the pointy hat, flying broomstick and bubbling cauldron. The origins of these ideas have been widely discussed with one theory being the associations with the brewing of ale in medieval Europe. Women called ‘Alewives’ would brew ale at home and sell it at local markets or their house. They would wear a tall, pointed hat that would stand out in a crowd and therefore entice shoppers into buying her goods. This marketing technique continued with the use of the broomstick. Alewives would lean a broomstick outside their home to let passersby know that there is ale for sale. The cauldron then comes into play as it could be seen bubbling inside the homes producing the ale for sale. As ale is an alcohol, thus it can change the way people act and if someone had too much of it, it may even make them ill. From this, the idea of broomsticks flying then comes into play as it is said that the witches’ potion (the ale) caused dreams where people would see the witches fly on their sticks. Witches were also believed to have powers that could change people or make them ill and are said to have mixed up potions in cauldrons just like the alewives brewed ale.

Cats – After making a deal with the devil and becoming a witch, the witches would be gifted an animal companion which would have magical powers. The animals often associated with witches were black cats, toads, rats, mice, owls, dogs, birds, goats, or even spiders, flies, or snails. These companions were known as ‘Imps’ or ‘Familiars’ and were believed to serve as messengers, general helpers and even spies. The Celts believed that cats were a reincarnation of humans who committed crimes or bad deeds in their past lives. This led to the idea of cats being involved in witchcraft.

Green skin - When people dress up as witches, they often paint their faces green. This, however, is a much more modern idea of a witch. The first portrayal of a green witch was in the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. The Wicked Witch of the West was painted green to make her stand out against other characters on the new Technicolour film technology. Although some witches have been depicted throughout history with oddly coloured skin such as red or orange, there is no historical significance to the green skin appearance of a witch.

Pentagram – A Pentagram is a star shaped symbol often associated with witchcraft due to its ancient folk tales and magical beliefs. It can be seen in various cultures and religions throughout history, but it originated from ancient Greece. The Celts and Norse people believed the edges of the Pentagram would protect them against evil spirits and misfortune. The five points on the pentagram represent different elements which are normally used during rituals. This may be the reason witches are associated so strongly with this symbol.

Fig. 1: The Three Witches from Macbeth, Daniel Gardner ca. 1775. Via the National Portrait Gallery, U.K.

Fig. 2: The History of Witches and Wizards, 1720. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Fig. 3: Three witches with a cat, a dog and a bird. Engraving, ca. 1800, after a woodcut, 1619.

Fig. 4: Wizard of Oz, Film, 1939, copyright Amazon MGM

Fig. 5: Eldridge, A. (2022). pentagram | Design, Shape, Star, Supernatural, Definition, & Meaning | Britannica.

Sources

Burgess, C. (2023). Why do witches have cats? A history of the witch’s familiar - History Bombs. [online] History Bombs. Available at: https://historybombs.com/2023/10/why-do-witches-have-cats-a-history-of-the-witchs-familiar/.

Crossroads, J. | D. (2019). The History and Symbolism of the Pentagram. [online] dualcrossroads. Available at: https://www.dualcrossroads.com/post/the-history-and-symbolism-of-the-pentagram.

Rizzo, J. (2024). How broomsticks, cauldrons, and pointy hats became essential witch gear. [online] History. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/witches-gear-broomstick-hat.

Rodriguez, L. (2014). Why Are Witches Green? [online] Boing Boing. Available at: https://boingboing.net/2014/10/29/why-are-witches-green.html.